The rediscovery in the late nineteenth century of the Assyrian Empire in the north of present-day Iraq and, soon after, the rediscovery of the Sumerian civilization in the south, all began with an archaeology intending to find the civilizations mentioned in the Hebrew Scriptures.

Although archaeology has gone its own way, the science of archaeology began with biblical archaeology. The exegesis – the critical explanation or analysis – of ancient sacred texts began with the religious exegesis of scripture. Religious exegesis is the intense religious study of sacred scripture.

Pious study vs Critical, Historical Exegesis

Every religion that has sacred texts, has its own tradition of study and evaluation of their texts; this detailed study of scripture has been at the heart of most religious practice.

I have mentioned in other posts that all serious believers tend to study their faith, their scriptures, and the history of their religion. From the simplest believer to the theologian, a struggle between study and belief can potentially dominate the believer’s life.

But, more to the point, the current study of a faith by the faithful necessarily opens up the controversies from which their religion was born. Intense study brings up conflicting interpretations of sacred texts and questions surround the beliefs of conflicting sects.

Over centuries of study, the scholarly examination of sacred texts has developed into an historical, critical approach. For anyone seeking to understand the religions of the world, it is important to distinguish between a theological or pious exegesis, and the critical, historical exegesis that does not assume the faith of the scholar.

In my Introduction to World Religions class I found it necessary to clarify the difference between religious studies and theology. It may be trivial to those in the field, but it was important to state in the introductory class that interest and study of religion is not equivalent to theology. Theology belongs to the faithful.

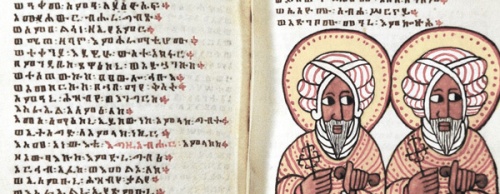

Pious exegesis exist as a long-standing tradition in every religion that possesses sacred texts. Many ancient explications of sacred texts have themselves become sacred. That is to say, some very pious explanations of sacred texts were later included as sacred texts themselves. A few examples follow.

In Hinduism, the Upanishads, which are normally included in, and were transmitted along with the Vedas, are a form of religious commentary, or religious exegesis, of the Vedas.

Much of Rabbinical Judaism is scholarly commentary on the Tanakh (The Hebrew Scriptures) and scholarly commentary on the commentary.

The ‘Zend’ of the Zend-Avestas of Zoroastrianism is commentary included with the Avestas sacred scriptures. Also called Avistak va Zand, which simply means ‘Avesta and Zend’, the combined version comes down to the present as an incomplete work.

The Avestas can be studied with or without the commentary, although it is difficult to find either in English translation.

Much of modern, non-pious exegesis consists of modern linguistic analysis of ancient religious texts. Modern exploration of ancient texts has uncovered the ways in which the texts have been altered in the process of being copied over the centuries.

But all of our sacred texts seem to make comprehension as difficult as possible for the reader. This process is, of course, compounded by the difficulties of translating ancient literature.

The Zend Avestas French translation, late 18th century, by the founder of École française d’Extrême-Orient, Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron

It is often said that ‘translation is treason’ and this is nowhere more true than in the translation of ancient poetry and poetic prose. In many cases, the ancient religious terminology has fallen out of use and their meanings cannot be retrieved.

I have found that some religious terms are used and repeated among the adherents (and even the experts) of a religion without any knowledge of their meaning or origin. Even the authorities on religious scriptures readily confess their doubts that certain meanings will ever be recovered when studying the Zoroastrian Avestas, the Vedas, the Tanakh, the I Ching or the ancient Babylonian and Egyptian texts.